This cover story appeared in the 2021 issue of Mid-South Super Lawyers magazine.

‘All The Fun Cases’ – Judy Simmons Henry has battled cults and Ponzi schemes, and now reps NCAA players and coaches, too

Judy Simmons Henry likes to tell young lawyers to be in the office Friday afternoons. She’s not micromanaging—it’s a little secret for those who wish to become advisers to CEOs, as Henry herself desired in the early 1980s.

It was at Wright Lindsey Jennings, her first and only firm, that Henry figured it out: Friday afternoons are when decision makers pick up the phone to address the thing that’s been stewing on their desk all week. One such afternoon, she found herself talking to the president of Arkansas’ largest bank.

“It was about a very distressed loan,” Henry says. “I uncovered bank fraud and what I thought was going to be a huge lawsuit that had been set up against the financial institution. And sure enough, that’s exactly what it was. I had been a real lawyer out in the litigation world for three months, yet they wanted me to lead the case.”

The borrower, a 100-year-old family-owned hardware store, filed a $20 million lawsuit against National Bank of Commerce, which Henry successfully defended for five years. In the end, lender liability would become a staple of her eclectic business litigation practice.

“I can remember her telling us she wanted to represent major corporations on the biggest cases they had,” says WLJ partner Charles T. Coleman about Henry’s initial interview with the firm. “All that could go through my mind was ‘That’s not very realistic.’ And then she started talking about how she wanted to represent NFL athletes—that she thought athletes needed someone who would look out for their best interests and she didn’t think that was happening at this time, and again I was thinking, ‘That’s pretty presumptive of this young lady.’”

It wasn’t. For a decade, Henry was a certified NFL Players Association agent, reinvigorating her firm’s sports law practice. In 2019, Henry negotiated the deal that made Sam Pittman the Razorbacks football coach. She proudly adds that both her husband and son played football at Arkansas.

“I’m told I’m the only female that has ever represented a head football coach in the SEC,” she says. “I think it’s a really positive step for women in the industry.”

“She’s not your traditional SEC coaches’ agent,” says Arkansas Athletic Director Hunter Yurachek. He says Henry was respectfully persistent in bringing Pittman to his attention, campaigning behind the scenes with her many Little Rock connections to make sure she got his ear, then moving quickly to get his contract negotiated late into a Sunday night. “There’s one agent that has 11 of the 14 head coaches in the SEC, and that’s not Judy. She’s atypical in this space.”

Troy Wells, president and CEO of Baptist Health, the state’s largest health care organization, says Henry’s leadership as an adviser and board member makes everyone better. “As a CEO, it is challenging having her in the room because she stays one step ahead of you and everyone else,” he says. “Unique to Judy is the ability to do this while maintaining a caring and compassionate spirit.”

“She is definitely a trailblazer in business litigation,” says WLJ managing partner Stephen R. Lancaster. “She is one of those rare sorts that can do anything and does. She’s really a cornerstone of our firm, both professionally and personally. We couldn’t do it without her. And we really wouldn’t want to.”

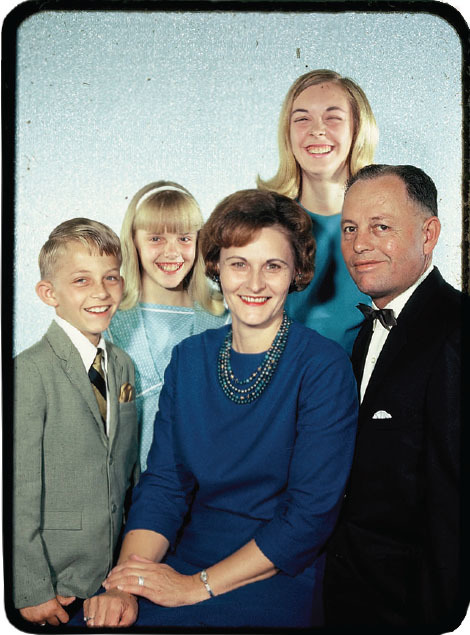

As a child growing up outside the city limits of Texarkana (“‘in the country’ is the way it was said,” Henry adds), Henry could be found hanging upside-down from monkey bars, climbing the tallest trees, or gathering with other kids to play softball, kickball, football, tetherball— anything with a ball, really. On Sundays, after her family went to church, she and her dad would run to the den, and, if they could get the antenna just right, watch the Dallas Cowboys.

Naturally athletic, she found an old balance beam in the corner of her school gym one day, pulled it out, and taught herself gymnastics. She competed throughout junior high and high school, earning All-American honors, and wound up attending the University of Central Arkansas on a gymnastics scholarship. Her plan was to become a pediatrician.

It was a professor in her master’s program at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, who handed her a book on sports law and said she should read it. At the time, Henry was also coaching the university’s women’s club gymnastics team, traveling for competitions and teaching youth in the community. Reading another book, particularly a law book, was the furthest thing from her mind. But she found herself engrossed. It was the first time it registered that the law had real-world implications, and that the physical education classes she loved so much as a girl were the result of policy.

“I grew up under Title IX,” she says. “I got to watch sports go from nothing for girls to a full array of sports being made available—giving us an opportunity to make new friends and learn the skills that it takes to work as a team on a common goal. Without Title IX, there probably would not have been a gymnastics program in my school system or an opportunity for me to compete.”

During law school, she spent a summer as a staffer for U.S. Sen. David Pryor. On weekends that summer, Henry would visit a friend from graduate school whose father was Don Breaux, the offensive backfield coach for Washington’s NFL team. Henry would follow Coach Breaux around, picking up a trail of napkins and scraps of papers marked with Xs and Os, and they would talk all things NFL, including collective bargaining agreements and negotiations.

“Players were represented by their fathers or their uncles, or somebody who was an agent but not a licensed attorney,” she says. “I had only been in law school a year, but I knew enough to know that every single word in that contract meant something. It did not seem right for players to be represented by non-attorneys. I made the decision then that I should do this and do it well.”

First, she knew, she needed to become a solid business lawyer and litigator. In the years following the National Bank of Commerce case, she was just that, having, at any given time, one to five big lender-liability suits on her desk. She was also following the money trail of an infamous cult.

“It seems like she gets a lot of the fun cases,” Coleman says.

Tony Alamo was an apocalyptic preacher with a large Alma, Arkansas, compound who persuaded thousands of followers to donate all their worldly goods to his ministry. (He died in prison in 2017 after being convicted on Mann Act charges.) Henry represented two men who sought counsel after one of their boys had been paddled at a religious service until blood ran down his leg. Alamo had also begun taking multiple wives—including theirs.

“We helped our men and children escape the compound,” Henry says. “The men left one night and then the task was to get the children out. The children believed their fathers were dead. They were told their fathers had been killed in some sort of robbery. Their mothers never left.”

Henry’s clients received a multimillion-dollar judgment on fair-labor wage violations; they had worked without pay ripping the seams from blue jeans to make high-end Alamo jackets that were airbrushed by artists, studded with rhinestones and sold to celebrities like Madonna and Mr. T. To collect on those judgments, Henry had to find and liquidate assets hidden around the country. She wound up putting thousands of the jackets in cold storage, but days before the intended sale she got a call from the storage facility that her units were open and empty.

“As it turned out, the IRS took my jackets,” she says. “They had judgments against the Alamos for tax evasion—because I had pierced through all their nonprofit agencies and busted them as for-profit. So I had to sue the IRS to get my jackets back.”

Henry laughs at the bizarreness of the case. She would come out of church and find Alamo flyers, denouncing her as an anti-religious zealot, stuck in the windshields of all the cars. In the end, it took 10 years, but she collected all the judgments.

“Did that satisfy the damage?” she says. “No. Those children will never be the same. But at least it gave them the ability for a fresh start. That case lasted 10 years, and I learned so much about how people can manipulate and distort the truth, and how important it is to stay grounded. A lot of people lost their way in that alleged ministry.”

In another multimillion-dollar case, a family was involved in a car accident in which one of their children was decapitated, but the lawyer they hired turned out to be a crook. Not only had he never never filed an injury claim for them, Henry uncovered that he was involved in a scheme selling phones manipulated in Honduras to tap into other people’s lines, making the calls free to the buyers. She brought the court FAA records showing the locations of his airplanes and was granted a restraining order that they be tied down. The next day, when Henry and her husband returned home from watching their boys play soccer, they saw something scattered all over the front yard. At first, they thought local teens must have “forked” them—a prank involving forks instead of toilet paper. But it wasn’t forks; it was Honduran money.

“That was a little warning to me that this lawyer, or somebody connected with him, knew where I lived,” she says. “That led to contact with the FBI. … I remember leaving the office really late one night, thinking someone was following me, and it was an FBI agent. They had gotten other tips.”

Henry isn’t sure why civil cases with criminal implications seem to gravitate toward her, but colleagues say it’s no accident. It’s her attention to detail, and the way she tenaciously pulls at a string until a whole story unravels, says WLJ partner and COO Adrienne L. Baker.

Case in point: When Baker was a new attorney, Henry invited her to help represent a man in Florida who had come to them after losing money in an investment in Arkansas. To Baker, it looked like a normal debt case.

“Judy said, ‘No, I think there’s something more to it,’ so we started digging and doing discovery and kept finding things that didn’t look right,” Baker recalls. “Eventually we uncovered a Ponzi scheme with a web of people involved. We started going after them. We chased them into bankruptcy court and the judge got law enforcement involved, which led to criminal charges being filed. We ended up finding over 500 entities, incorporated across the U.S. as shell companies to hide and funnel money to parts unknown. If it hadn’t been for her saying ‘Something doesn’t smell right, we need to keep pulling at this thread,’ our client never would have known that this Ponzi scheme existed.”

“If she gets on to something, she’s going to run it to the ground,” Lancaster says. “People know when they’ve been in a deposition with Judy that you better know what you’re talking about and you better tell the truth. She’s going to get it one way or another.”

After 20 years building her business lit practice and raising two boys, Henry decided it was time to pursue her other dream. So in 2009, she passed the exam to become an NFL Players Association certified contract adviser.

Coleman still remembers when she found him at the office to tell him the news. “The effort she put into that endeavor was pretty amazing,” he says. “She had young lawyers here in the firm, who were of course interested in that kind of practice, lining up. And, boy, they worked tirelessly.”

It’s been a constantly evolving practice. In 2013, when the NFLPA rules changed so that only certified agents could meet with players—meaning Henry could no longer operate as a team with firm colleagues—she decided to transition to representing only coaches. Then this July, in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma, the NCAA lifted its restrictions on players receiving compensation for the use of their names, images and likenesses (NIL). Henry and others at the firm quickly held their first NIL meetings with athletes and businesses, and by the end of September had signed on 11 student-athlete and business clients. She’s seeing everything from cash deals to apparel, gift cards and donations toward foundations. Sometimes all of the above.

While Henry does have her concerns about full-time student-athletes running what is essentially a business with contractual requirements, she loves representing players. She has even decided to renew her NFLPA’s license to continue representing these clients in the event they turn pro.

“She knows personally what these athletes go through, what they have to do to prepare themselves for—life following college sports—so she takes almost a maternal interest in this particular group of clients,” says Ed L. Lowther Jr., who served as WLJ’s managing partner for 15 years.

She does the same as a mentor to young women lawyers, says Baker, as well as young women generally. When Regina Hopper, a law school colleague, became CEO of Miss America during the early stages of #MeToo, she called on Henry to help her rebrand. The resulting changes removed beauty from the competition and focused on the social impact candidates have had. The 2020 Miss America, for example, was a biochemist who spoke about fighting the opioid crisis. Her knowledge as a scientist came in handy during the COVID-19 pandemic as well.

“Judy understood the importance of what we were trying to do for young women,” Hopper says. “The focus of the program is not about choosing Miss America so that one woman wins a title. In the program, everyone wins a scholarship. She cares about women and opportunities for women.”

Glen Jones, senior adviser to the president at Georgetown University, who has served on the Baptist Health board with Henry, calls her a person of remarkable character, whose integrity shines through particularly when difficult decisions have to be made.

“She truly empathizes with people,” Jones says. “She has a concern for those who have been left behind in society, and she utilizes her position, her influence, not for herself but for other people. … I think it’s something our world needs more of right now.”