Categories

The article appeared in the July 7, 2025, issue of Arkansas Business, featuring WLJ Banking Law partner Jake Fair.

Bankruptcy filings are rising across the board in Arkansas, but family farm bankruptcies are “skyrocketing.”

That’s the assessment of Joel Hargis of the Caddell Reynolds Law Firm’s Jonesboro office. Hargis, who became a lawyer in 2004, regularly handles Chapter 12 bankruptcy cases.

Chapter 12 offers relief to troubled family farms and family fishermen with regular annual income, he said.

“I have another three Chapter 12s that I’m preparing to file within the next two weeks,” he told Arkansas Business recently.

Hargis’ row crop clients across the state are “hurting,” he said. “I mean, they’re hurting badly.”

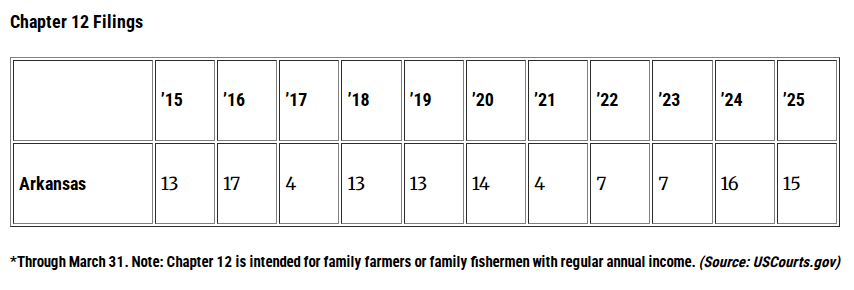

For the quarter that ended March 31, 15 Chapter 12 bankruptcies were filed in Arkansas. That pace is on track to easily surpass the filings for all of last year, which totaled 16, according to the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts.

Farm bankruptcies in the state are likely to eclipse the worst year in the past decade: 17 Chapter 12 cases filed in 2017.

The reason behind the increase in filings? Commodity prices farmers receive have been “declining tremendously, and those inputs kept going up,” said Ryan Loy, an extension economist with the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture. He said it was “pretty staggering to see that an entire year’s worth of Chapter 12s in the first quarter of this year. That is very eye-opening.”

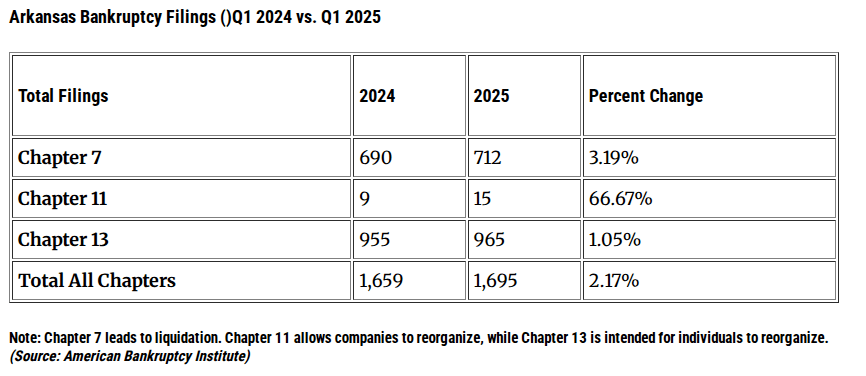

Meanwhile, Chapter 11 bankruptcies, which allow companies to reorganize, shot up 67% in the first quarter of 2025 compared with the same period a year ago. The quarter saw 15 Chapter 11s filed in Arkansas, according to the American Bankruptcy Institute of Alexandria, Virginia.

Chapter 11 filings are also rising across the country. Attorneys filed 733 Chapter 11s in May, an increase of 62% from April, according to information from Epiq AACER, which provides U.S. bankruptcy figures.

“The sharp uptick in overall commercial chapter 11 filings in May 2025 underscores the ongoing economic pressures businesses face, from elevated borrower costs, potential tariff impacts and geopolitical uncertainty,” Michael Hunter, vice president of Epiq AACER, said in a news release.

Nevertheless, the number of Chapter 11 filings in the U.S. in May was down 4% from May 2024, the news release said.

Ed Flynn, a consultant at the American Bankruptcy Institute, told Arkansas Business in April that he expects the number of bankruptcies to increase nationwide later this year and into next year.

“I assume that there will be some substantial tariffs in place and that will affect employment, inflation,” he said. “I don’t think consumers, or even businesses, have maybe really felt the pain of what may be coming.”

Uncertainty remains surrounding the tariffs and cuts in government services such as Medicaid.

“It just seems to me that it could be tough times for a lot of consumers ahead, but you know, it will take a little time before that shows up in bankruptcy courts,” Flynn said, “because people don’t file bankruptcy the day they lose their job or the day they incur debt or fall behind on debt.”

The rise of bankruptcies in Arkansas doesn’t surprise Jake Fair, an attorney with Wright Lindsey Jennings’ Little Rock office who represents creditors in bankruptcy cases. He’s seen more Chapter 12 cases filed recently than he has in his 11 years of practice. “I suspect most lenders are having more problems with those portfolios than they did before,” he said.

Warning Issued

In July 2024, several people in the agriculture industry warned the U.S. House Committee on Agriculture about the looming crisis facing farmers across the country.

“Plummeting crop prices, escalating input costs, worsening credit conditions, and sustained natural disasters are creating a ‘perfect storm’ of headwinds for farm country,” said a news release from the chairman of the committee, U.S. Rep. Glenn “GT” Thompson, R-Pa.

David Dunlow, chairman of the American Cotton Producers, testified before the committee that it was the worst time in his 40 years of farming. “Inputs such as labor, supplies, equipment, parts, fuel, land rent, fertilizer and seed have skyrocketed,” Dunlow said at the committee meeting. “Some of these expenses have nearly doubled, and my margins have narrowed over the last several years. Things have gotten so bad that these days a bumper crop is required just to break even.”

In Arkansas, the number of Chapter 12 bankruptcies started rising in 2024, when 16 were filed, up from seven in 2023.

Around 2023, the spread began to widen between the crop prices farmers received and their expenses for operating the farm, including fertilizer, labor, equipment and fuel, said Loy, with the UA Division of Agriculture.

“If you have the same input price you had over the last few years with lower commodity prices, you just can’t pay back your debts as efficiently as maybe you could have when you got into it and got that loan originally,” Loy said.

Farmers are “just lamenting that they can’t make it, not in this economic climate, and not without help from Congress,” Hargis said.

In December, Congress passed the American Relief Act, which continued the 2018 Farm Bill through Sept. 30. The Farm Bill’s “safety net and price support programs provide peace of mind for producers who are working to manage market ups and downs,” according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s website.

The extension of the bill provides “access to credit to help start, improve, expand, and strengthen American farms,” the website said.

Farm sector net income was forecast to fall for the second consecutive year in 2024 to $139.1 billion, down from $147.3 billion in 2023, according to the USDA. Meanwhile, expenses were forecast at $452.9 billion in 2024, a decrease of 2% from 2023. But expenses were nearly 22% higher than 2021.

“There’s so many different angles of why everything’s so expensive right now,” Loy said.

Larger-scale farm operations that have more assets can better absorb the rising costs and lower crop prices than smaller family farmers, he said.

Filing Chapter 12

In a Chapter 12 bankruptcy, farmers will propose a plan to repay in installments all or parts of their debt over three to five years, the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts’ website said. The total debts can’t be more than $12.56 million to qualify for a Chapter 12 bankruptcy.

“We don’t even have to necessarily cure a default on a loan over the three- to five-year plan term,” Hargis said. “We’ve just got to be able to get money flowing to creditors.”

Once the reorganization plan is approved by the bankruptcy court, the farmer will make payments to the trustee.

Hargis said that if farmers are proactive, they have a better chance of having a successful reorganization in Chapter 12. “If they don’t come in until everybody’s starting to sue them, they’re going to have a tougher time maneuvering to Chapter 12, because … the notes have been called, [and] we’re concerned about losing property.”

Wright Lindsey Jennings’ Fair said that a lot of his creditor clients want to be good lenders and work with the borrowers because “it’s in their interest for them to succeed.”

Still, the advice Fair is giving his clients is to look at their collateral and make sure they know what it is and where it is. And if it’s real property, the lender should know what it’s worth and make sure the documentation is in order. “I think it’s especially true when filings are up like they are right now,” Fair said.

The last thing a lender wants to be is a landlord or stuck with equipment that would need to be sold to pay off a loan, he said.

“One thing that’s important to highlight is that farmers are resilient,” Loy said.

But this year’s harvests will determine farmers’ financial condition for the remainder of the year and into next year, he said.

“If this disparity between prices that they’re paying to grow the crop versus what they’re receiving, if that continues into perpetuity, there’s no way that bankruptcies decline,” Loy said, “other than there’s no more farms to actually declare bankruptcy.”